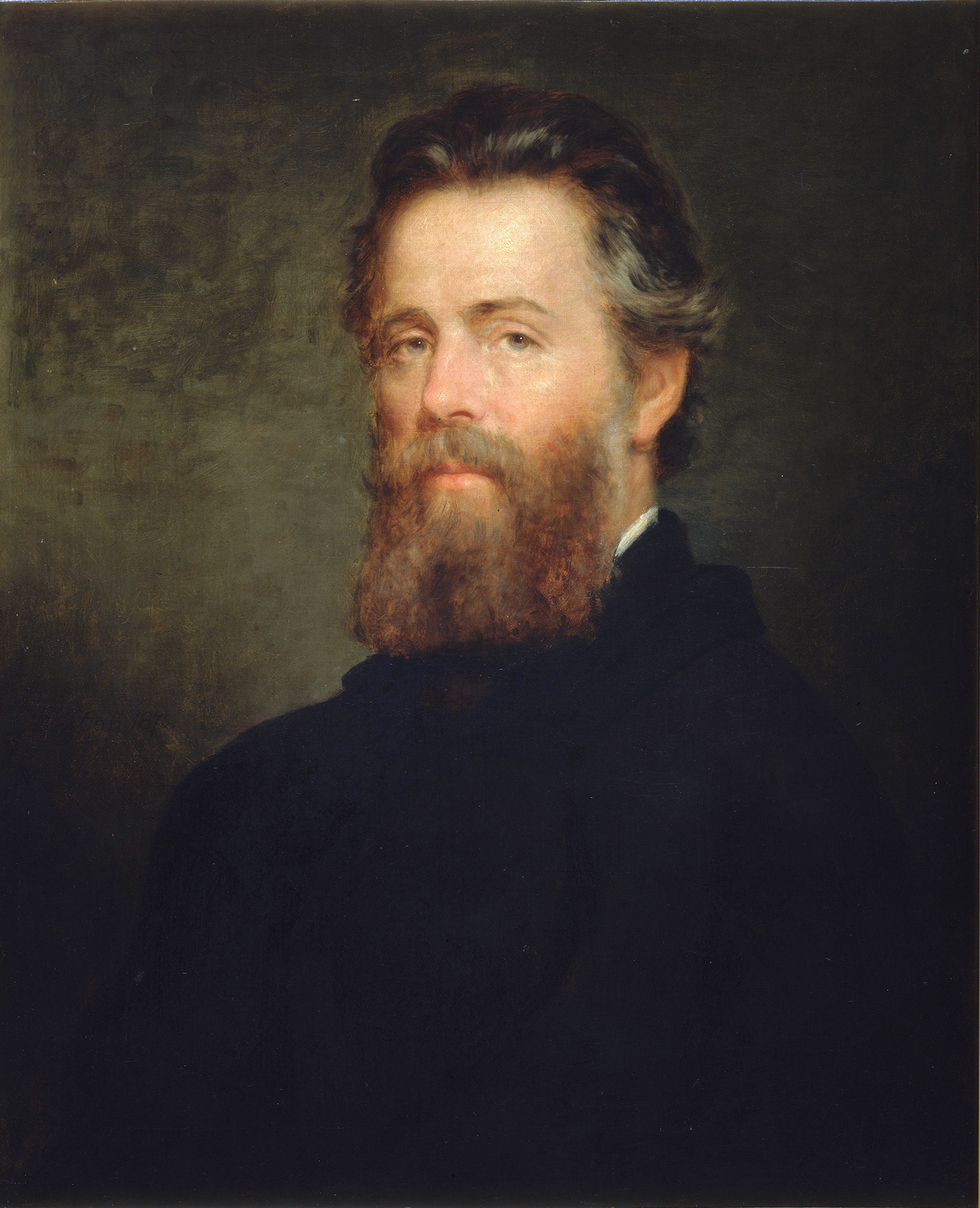

Herman Melville najznámejšie citáty

Herman Melville: Citáty v angličtine

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 157

Kontext: In me divine magnanimities are spontaneous and instantaneous — catch them while you can. The world goes round, and the other side comes up. So now I can't write what I felt. But I felt pantheistic then—your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God's. A sense of unspeakable security is in me this moment, on account of your having understood the book. I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb. Ineffable socialities are in me. I would sit down and dine with you and all the Gods in old Rome's Pantheon. It is a strange feeling — no hopelessness is in it, no despair. Content — that is it; and irresponsibility; but without licentious inclination. I speak now of my profoundest sense of being, not of an incidental feeling.

Zdroj: Billy Budd, the Sailor (1891), Ch. 28

Kontext: The symmetry of form attainable in pure fiction can not so readily be achieved in a narration essentially having less to do with fable than with fact. Truth uncompromisingly told will always have its ragged edges...

Zdroj: Moby-Dick: or, the Whale (1851), Ch. 17 : The Ramadan

Kontext: I have no objection to any person’s religion, be it what it may, so long as that person does not kill or insult any other person, because that other person don’t believe it also. But when a man’s religion becomes really frantic; when it is a positive torment to him; and, in fine, makes this earth of ours an uncomfortable inn to lodge in; then I think it high time to take that individual aside and argue the point with him.

Letter to Evert Augustus Duyckinck (3 March 1849); published in The Letters of Herman Melville (1960) edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman, p. 78; a portion of this is sometimes modernized in two ways:

Kontext: I do not oscillate in Emerson's rainbow, but prefer rather to hang myself in mine own halter than swing in any other man's swing. Yet I think Emerson is more than a brilliant fellow. Be his stuff begged, borrowed, or stolen, or of his own domestic manufacture he is an uncommon man. Swear he is a humbug — then is he no common humbug. Lay it down that had not Sir Thomas Browne lived, Emerson would not have mystified — I will answer, that had not Old Zack's father begot him, old Zack would never have been the hero of Palo Alto. The truth is that we are all sons, grandsons, or nephews or great-nephews of those who go before us. No one is his own sire. — I was very agreeably disappointed in Mr Emerson. I had heard of him as full of transcendentalisms, myths & oracular gibberish; I had only glanced at a book of his once in Putnam's store — that was all I knew of him, till I heard him lecture. — To my surprise, I found him quite intelligible, tho' to say truth, they told me that that night he was unusually plain. — Now, there is a something about every man elevated above mediocrity, which is, for the most part, instinctuly perceptible. This I see in Mr Emerson. And, frankly, for the sake of the argument, let us call him a fool; — then had I rather be a fool than a wise man. —I love all men who dive. Any fish can swim near the surface, but it takes a great whale to go down stairs five miles or more; & if he don't attain the bottom, why, all the lead in Galena can't fashion the plumet that will. I'm not talking of Mr Emerson now — but of the whole corps of thought-divers, that have been diving & coming up again with bloodshot eyes since the world began.

I could readily see in Emerson, notwithstanding his merit, a gaping flaw. It was, the insinuation, that had he lived in those days when the world was made, he might have offered some valuable suggestions. These men are all cracked right across the brow. And never will the pullers-down be able to cope with the builders-up. And this pulling down is easy enough — a keg of powder blew up Block's Monument — but the man who applied the match, could not, alone, build such a pile to save his soul from the shark-maw of the Devil. But enough of this Plato who talks thro' his nose.

Letter to Evert Augustus Duyckinck (3 March 1849); published in The Letters of Herman Melville (1960) edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman, p. 79

Kontext: And do not think, my boy, that because I, impulsively broke forth in jubillations over Shakspeare, that, therefore, I am of the number of the snobs who burn their tuns of rancid fat at his shrine. No, I would stand afar off & alone, & burn some pure Palm oil, the product of some overtopping trunk. — I would to God Shakspeare had lived later, & promenaded in Broadway. Not that I might have had the pleasure of leaving my card for him at the Astor, or made merry with him over a bowl of the fine Duyckinck punch; but that the muzzle which all men wore on their soul in the Elizebethan day, might not have intercepted Shakspers full articulations. For I hold it a verity, that even Shakspeare, was not a frank man to the uttermost. And, indeed, who in this intolerant universe is, or can be? But the Declaration of Independence makes a difference.—There, I have driven my horse so hard that I have made my inn before sundown.

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 157 <!-- also in Herman Melville, Mariner and Mystic (1921) by Raymond Melbourne Weaver -->

Kontext: Not one man in five cycles, who is wise, will expect appreciative recognition from his fellows, or any one of them. Appreciation! Recognition! Is love appreciated? Why, ever since Adam, who has got to the meaning of this great allegory — the world? Then we pigmies must be content to have our paper allegories but ill comprehended.

“I would to God Shakspeare had lived later, & promenaded in Broadway.”

Letter to Evert Augustus Duyckinck (3 March 1849); published in The Letters of Herman Melville (1960) edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman, p. 79

Kontext: And do not think, my boy, that because I, impulsively broke forth in jubillations over Shakspeare, that, therefore, I am of the number of the snobs who burn their tuns of rancid fat at his shrine. No, I would stand afar off & alone, & burn some pure Palm oil, the product of some overtopping trunk. — I would to God Shakspeare had lived later, & promenaded in Broadway. Not that I might have had the pleasure of leaving my card for him at the Astor, or made merry with him over a bowl of the fine Duyckinck punch; but that the muzzle which all men wore on their soul in the Elizebethan day, might not have intercepted Shakspers full articulations. For I hold it a verity, that even Shakspeare, was not a frank man to the uttermost. And, indeed, who in this intolerant universe is, or can be? But the Declaration of Independence makes a difference.—There, I have driven my horse so hard that I have made my inn before sundown.

Letter to Evert Augustus Duyckinck (3 March 1849); published in The Letters of Herman Melville (1960) edited by Merrell R. Davis and William H. Gilman, p. 78; a portion of this is sometimes modernized in two ways:

Kontext: I do not oscillate in Emerson's rainbow, but prefer rather to hang myself in mine own halter than swing in any other man's swing. Yet I think Emerson is more than a brilliant fellow. Be his stuff begged, borrowed, or stolen, or of his own domestic manufacture he is an uncommon man. Swear he is a humbug — then is he no common humbug. Lay it down that had not Sir Thomas Browne lived, Emerson would not have mystified — I will answer, that had not Old Zack's father begot him, old Zack would never have been the hero of Palo Alto. The truth is that we are all sons, grandsons, or nephews or great-nephews of those who go before us. No one is his own sire. — I was very agreeably disappointed in Mr Emerson. I had heard of him as full of transcendentalisms, myths & oracular gibberish; I had only glanced at a book of his once in Putnam's store — that was all I knew of him, till I heard him lecture. — To my surprise, I found him quite intelligible, tho' to say truth, they told me that that night he was unusually plain. — Now, there is a something about every man elevated above mediocrity, which is, for the most part, instinctuly perceptible. This I see in Mr Emerson. And, frankly, for the sake of the argument, let us call him a fool; — then had I rather be a fool than a wise man. —I love all men who dive. Any fish can swim near the surface, but it takes a great whale to go down stairs five miles or more; & if he don't attain the bottom, why, all the lead in Galena can't fashion the plumet that will. I'm not talking of Mr Emerson now — but of the whole corps of thought-divers, that have been diving & coming up again with bloodshot eyes since the world began.

I could readily see in Emerson, notwithstanding his merit, a gaping flaw. It was, the insinuation, that had he lived in those days when the world was made, he might have offered some valuable suggestions. These men are all cracked right across the brow. And never will the pullers-down be able to cope with the builders-up. And this pulling down is easy enough — a keg of powder blew up Block's Monument — but the man who applied the match, could not, alone, build such a pile to save his soul from the shark-maw of the Devil. But enough of this Plato who talks thro' his nose.

“And perhaps, after all, there is no secret.”

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, including bits of a review of his work that he had written (c. 16 April 1851); published in Nathaniel Hawthorne and His WIfe Vol, I (1884) by Julian Hawthorne, Ch. VIII : Lenox, p. 388

Kontext: There is a certain tragic phase of humanity which, in our opinion, was never more powerfully embodied than by Hawthorne. We mean the tragedies of human thought in its own unbiassed, native, and profounder workings. We think that into no recorded mind has the intense feeling of the usable truth ever entered more deeply than into this man's. By usable truth, we mean the apprehension of the absolute condition of present things as they strike the eye of the man who fears them not, though they do their worst to him, — the man who, like Russia or the British Empire, declares himself a sovereign nature (in himself) amid the powers of heaven, hell, and earth. He may perish; but so long as he exists he insists upon treating with all Powers upon an equal basis. If any of those other Powers choose to withhold certain secrets, let them; that does not impair my sovereignty in myself; that does not make me tributary. And perhaps, after all, there is no secret. We incline to think that the Problem of the Universe is like the Freemason's mighty secret, so terrible to all children. It turns out, at last, to consist in a triangle, a mallet, and an apron, — nothing more! We incline to think that God cannot explain His own secrets, and that He would like a little information upon certain points Himself. We mortals astonish Him as much as He us. But it is this Being of the matter; there lies the knot with which we choke ourselves. As soon as you say Me, a God, a Nature, so soon you jump off from your stool and hang from the beam. Yes, that word is the hangman. Take God out of the dictionary, and you would have Him in the street.

There is the grand truth about Nathaniel Hawthorne. He says NO! in thunder; but the Devil himself cannot make him say yes. For all men who say yes, lie; and all men who say no,—why, they are in the happy condition of judicious, unincumbered travellers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet-bag, — that is to say, the Ego. Whereas those yes-gentry, they travel with heaps of baggage, and, damn them! they will never get through the Custom House. What's the reason, Mr. Hawthorne, that in the last stages of metaphysics a fellow always falls to swearing so? I could rip an hour.

The last sentence is a quotation of Nathaniel Hawthorne

Hawthorne and His Mosses (1850)

Kontext: Would that all excellent books were foundlings, without father or mother, that so it might be, we could glorify them, without including their ostensible authors. Nor would any true man take exception to this; — least of all, he who writes, — "When the Artist rises high enough to achieve the Beautiful, the symbol by which he makes it perceptible to mortal senses becomes of little value in his eyes, while his spirit possesses itself in the enjoyment of the reality."

“It will be a strange sort of book”

On Moby-Dick, in a letter to Richard Henry Dana, Jr. (1 May 1850)

Kontext: It will be a strange sort of book, tho', I fear; blubber is blubber you know; tho' you may get oil out of it, the poetry runs as hard as sap from a frozen maple tree; — & to cook the thing up, one must needs throw in a little fancy, which from the nature of the thing, must be ungainly as the gambols of the whales themselves. Yet I mean to give the truth of the thing, spite of this.

“In me divine magnanimities are spontaneous and instantaneous — catch them while you can.”

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 157

Kontext: In me divine magnanimities are spontaneous and instantaneous — catch them while you can. The world goes round, and the other side comes up. So now I can't write what I felt. But I felt pantheistic then—your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God's. A sense of unspeakable security is in me this moment, on account of your having understood the book. I have written a wicked book, and feel spotless as the lamb. Ineffable socialities are in me. I would sit down and dine with you and all the Gods in old Rome's Pantheon. It is a strange feeling — no hopelessness is in it, no despair. Content — that is it; and irresponsibility; but without licentious inclination. I speak now of my profoundest sense of being, not of an incidental feeling.

Zdroj: Billy Budd, the Sailor (1891), Ch. 21

Kontext: In the light of that martial code whereby it was formally to be judged, innocence and guilt personified in Claggart and Budd in effect changed places. In a legal view the apparent victim of the tragedy was he who had sought to victimize a man blameless; and the indisputable deed of the latter, navally regarded, constituted the most heinous of military crimes.

“Leviathan is not the biggest fish; — I have heard of Krakens.”

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 1851); published in Memories of Hawthorne (1897) by Rose Hawthorne Lathrop, p. 158

Kontext: I am heartily sorry I ever wrote anything about you — it was paltry. Lord, when shall we be done growing? As long as we have anything more to do, we have done nothing. So, now, let us add Moby-Dick to our blessing, and step from that. Leviathan is not the biggest fish; — I have heard of Krakens.

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, including bits of a review of his work that he had written (c. 16 April 1851); published in Nathaniel Hawthorne and His WIfe Vol, I (1884) by Julian Hawthorne, Ch. VIII : Lenox, p. 388

Kontext: There is a certain tragic phase of humanity which, in our opinion, was never more powerfully embodied than by Hawthorne. We mean the tragedies of human thought in its own unbiassed, native, and profounder workings. We think that into no recorded mind has the intense feeling of the usable truth ever entered more deeply than into this man's. By usable truth, we mean the apprehension of the absolute condition of present things as they strike the eye of the man who fears them not, though they do their worst to him, — the man who, like Russia or the British Empire, declares himself a sovereign nature (in himself) amid the powers of heaven, hell, and earth. He may perish; but so long as he exists he insists upon treating with all Powers upon an equal basis. If any of those other Powers choose to withhold certain secrets, let them; that does not impair my sovereignty in myself; that does not make me tributary. And perhaps, after all, there is no secret. We incline to think that the Problem of the Universe is like the Freemason's mighty secret, so terrible to all children. It turns out, at last, to consist in a triangle, a mallet, and an apron, — nothing more! We incline to think that God cannot explain His own secrets, and that He would like a little information upon certain points Himself. We mortals astonish Him as much as He us. But it is this Being of the matter; there lies the knot with which we choke ourselves. As soon as you say Me, a God, a Nature, so soon you jump off from your stool and hang from the beam. Yes, that word is the hangman. Take God out of the dictionary, and you would have Him in the street.

There is the grand truth about Nathaniel Hawthorne. He says NO! in thunder; but the Devil himself cannot make him say yes. For all men who say yes, lie; and all men who say no,—why, they are in the happy condition of judicious, unincumbered travellers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet-bag, — that is to say, the Ego. Whereas those yes-gentry, they travel with heaps of baggage, and, damn them! they will never get through the Custom House. What's the reason, Mr. Hawthorne, that in the last stages of metaphysics a fellow always falls to swearing so? I could rip an hour.

Zdroj: The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (1857), Ch. 45

Kontext: I cannot tell you how thankful I am for your reminding me about the apocrypha here. For the moment, its being such escaped me. Fact is, when all is bound up together, it's sometimes confusing. The uncanonical part should be bound distinct. And, now that I think of it, how well did those learned doctors who rejected for us this whole book of Sirach. I never read anything so calculated to destroy man's confidence in man. This son of Sirach even says — I saw it but just now: 'Take heed of thy friends'; not, observe, thy seeming friends, thy hypocritical friends, thy false friends, but thy friends, thy real friends — that is to say, not the truest friend in the world is to be implicitly trusted. Can Rochefoucault equal that? I should not wonder if his view of human nature, like Machiavelli's, was taken from this Son of Sirach. And to call it wisdom — the Wisdom of the Son of Sirach! Wisdom, indeed! What an ugly thing wisdom must be! Give me the folly that dimples the cheek, say I, rather than the wisdom that curdles the blood. But no, no; it ain't wisdom; it's apocrypha, as you say, sir. For how can that be trustworthy that teaches distrust?

Letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne, including bits of a review of his work that he had written (c. 16 April 1851); published in Nathaniel Hawthorne and His WIfe Vol, I (1884) by Julian Hawthorne, Ch. VIII : Lenox, p. 388

Kontext: There is a certain tragic phase of humanity which, in our opinion, was never more powerfully embodied than by Hawthorne. We mean the tragedies of human thought in its own unbiassed, native, and profounder workings. We think that into no recorded mind has the intense feeling of the usable truth ever entered more deeply than into this man's. By usable truth, we mean the apprehension of the absolute condition of present things as they strike the eye of the man who fears them not, though they do their worst to him, — the man who, like Russia or the British Empire, declares himself a sovereign nature (in himself) amid the powers of heaven, hell, and earth. He may perish; but so long as he exists he insists upon treating with all Powers upon an equal basis. If any of those other Powers choose to withhold certain secrets, let them; that does not impair my sovereignty in myself; that does not make me tributary. And perhaps, after all, there is no secret. We incline to think that the Problem of the Universe is like the Freemason's mighty secret, so terrible to all children. It turns out, at last, to consist in a triangle, a mallet, and an apron, — nothing more! We incline to think that God cannot explain His own secrets, and that He would like a little information upon certain points Himself. We mortals astonish Him as much as He us. But it is this Being of the matter; there lies the knot with which we choke ourselves. As soon as you say Me, a God, a Nature, so soon you jump off from your stool and hang from the beam. Yes, that word is the hangman. Take God out of the dictionary, and you would have Him in the street.

There is the grand truth about Nathaniel Hawthorne. He says NO! in thunder; but the Devil himself cannot make him say yes. For all men who say yes, lie; and all men who say no,—why, they are in the happy condition of judicious, unincumbered travellers in Europe; they cross the frontiers into Eternity with nothing but a carpet-bag, — that is to say, the Ego. Whereas those yes-gentry, they travel with heaps of baggage, and, damn them! they will never get through the Custom House. What's the reason, Mr. Hawthorne, that in the last stages of metaphysics a fellow always falls to swearing so? I could rip an hour.

“Whoever is not in the possession of leisure can hardly be said to possess independence.”

Letter to Catherine G. Lansing (5 September 1877), published in The Melville Log : A Documentary Life of Herman Melville, 1819-1891 (1951) by Jay Leyda, Vol. 2, p. 765

Kontext: Whoever is not in the possession of leisure can hardly be said to possess independence. They talk of the dignity of work. Bosh. True Work is the necessity of poor humanity's earthly condition. The dignity is in leisure. Besides, 99 hundreths of all the work done in the world is either foolish and unnecessary, or harmful and wicked.

“All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks.”

Ahab to Starbuck, in Ch. 36 : The Quarter-Deck

Moby-Dick: or, the Whale (1851)

Kontext: All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event — in the living act, the undoubted deed — there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask.

“There is nothing nameable but that some men will undertake to do it for pay.”

Zdroj: Billy Budd, the Sailor (1891), Ch. 21

Kontext: Who in the rainbow can draw the line where the violet tint ends and the orange tint begins? Distinctly we see the difference of the colors, but where exactly does the one first blendingly enter into the other? So with sanity and insanity. In pronounced cases there is no question about them. But in some supposed cases, in various degrees supposedly less pronounced, to draw the exact line of demarcation few will undertake tho' for a fee some professional experts will. There is nothing nameable but that some men will undertake to do it for pay.

“Familiarity with danger makes a brave man braver, but less daring.”

Zdroj: White-Jacket (1850), Ch. 23

Kontext: Familiarity with danger makes a brave man braver, but less daring. Thus with seamen: he who goes the oftenest round Cape Horn goes the most circumspectly.

Poor Man's Pudding and Rich Man's Crumbs (1854)

“Talk not to me of blasphemy, man; I'd strike the sun if it insulted me.”

Zdroj: Moby-Dick or, The Whale