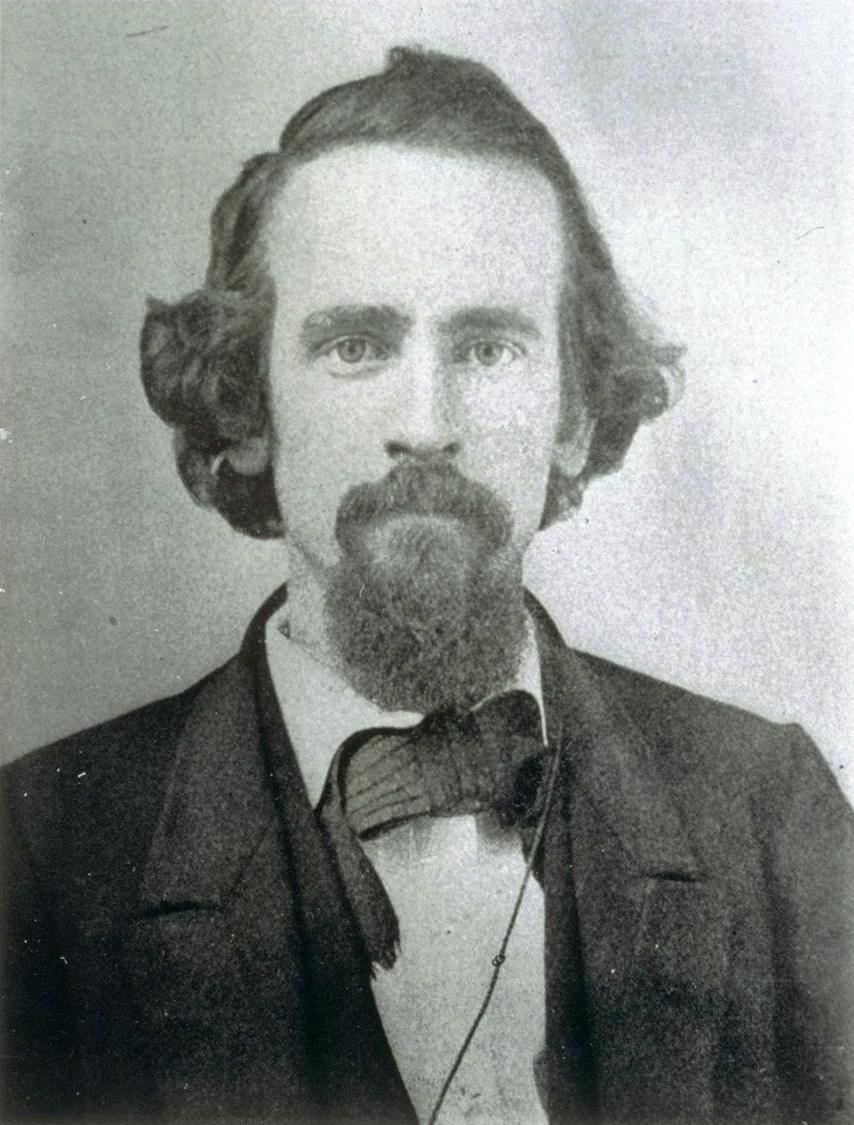

Henry George citáty a výroky

Henry George: Citáty v angličtine

Conclusion : The Moral of this Examination

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Kontext: It is not merely the authority of Mr. Spencer as a teacher on social subjects that I would discredit; but the blind reliance upon authority. For on such subjects the masses of men cannot safely trust authority. Given a wrong which affects the distribution of wealth and differentiates society into the rich and the poor, and the recognized organs of opinion and education, since they are dominated by the wealthy class, must necessarily represent the views and wishes of those who profit or imagine they profit by the wrong.

That thought on social questions is so confused and perplexed, that the aspirations of great bodies of men, deeply though vaguely conscious of injustice, are in all civilized countries being diverted to futile and dangerous remedies, is largely due to the fact that those who assume and are credited with superior knowledge of social and economic laws have devoted their powers, not to showing where the injustice lies but to hiding it; not to clearing common thought but to confusing it.

Zdroj: Social Problems (1883), Ch. 21 : Conclusion

Kontext: I am firmly convinced, as I have already said, that to effect any great social improvement, it is sympathy rather than self-interest, the sense of duty rather than the desire for self-advancement, that must be appealed to. Envy is akin to admiration, and it is the admiration that the rich and powerful excite which secures the perpetuation of aristocracies.

Part III : Recantation, Ch. XI Compensation

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Kontext: The primary error of the advocates of land nationalization is in their confusion of equal rights with joint rights, and in their consequent failure to realize the nature and meaning of economic rent… In truth the right to the use of land is not a joint or common right, but an equal right; the joint or common right is to rent, in the economic sense of the term. Therefore it is not necessary for the state to take land, it is only necessary for it to take rent. This taking by the commonalty of what is of common right, would of itself secure equality in what is of equal right — for since the holding of land could be profitable only to the user, there would be no inducement for any one to hold land that he could not adequately use, and monopolization being ended no one who wanted to use land would have any difficulty in finding it.

Zdroj: How to Help the Unemployed (1894), p. 179

Kontext: Why should charity be offered the unemployed? It is not alms they ask. They are insulted and embittered and degraded by being forced to accept as paupers what they would gladly earn as workers. What they ask is not charity, but the opportunity to use their own labor in satisfying their own wants. Why can they not have that? It is their natural right. He who made food and clothing and shelter necessary to man's life has also given to man, in the power of labor, the means of maintaining that life; and when, without fault of their own, men cannot exert that power, there is somewhere a wrong of the same kind as denial of the right of property and denial of the right of life — a wrong equivalent to robbery and murder on the grandest scale.

Charity can only palliate present suffering a little at the risk of fatal disease. For charity cannot right a wrong; only justice can do that. Charity is false, futile, and poisonous when offered as a substitute for justice.

Conclusion : The Moral of this Examination

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Kontext: I care nothing for creeds. I am not concerned with any one's religious belief. But I would have men think for themselves. If we do not, we can only abandon one superstition to take up another, and it may be a worse one. It is as bad for a man to think that he can know nothing as to think he knows all. There are things which it is given to all possessing reason to know, if they will but use that reason. And some things it may be there are, that — as was said by one whom the learning of the time sneered at, and the high priests persecuted, and polite society, speaking through the voice of those who knew not what they did, crucified — are hidden from the wise and prudent and revealed unto babes.

Zdroj: Social Problems (1883), Ch. 21 : Conclusion

Kontext: Many there are, too depressed, too embruted with hard toil and the struggle for animal existence, to think for themselves. Therefore the obligation devolves with all the more force on those who can. If thinking men are few, they are for that reason all the more powerful. Let no man imagine that he has no influence. Whoever he may be, and wherever he may be placed, the man who thinks becomes a light and a power. That for every idle word men may speak they shall give an account at the day of judgment, seems a hard saying. But what more clear than that the theory of the persistence of force, which teaches us that every movement continues to act and react, must apply as well to the universe of mind as to that of matter? Whoever becomes imbued with a noble idea kindles a flame from which other torches are lit, and influences those with whom he comes in contact, be they few or many. How far that influence, thus perpetuated, may extend, it is not given to him here to see. But it may be that the Lord of the Vineyard will know.

Introduction : The Reason for the Examination

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Kontext: The respect for authority, the presumption in favor of those who have won intellectual reputation, is within reasonable limits, both prudent and becoming. But it should not be carried too far, and there are some things especially as to which it behooves us all to use our own judgment and to maintain free minds. For not only does the history of the world show that undue deference to authority has been the potent agency through which errors have been enthroned and superstitions perpetuated, but there are regions of thought in which the largest powers and the greatest acquirements cannot guard against aberrations or assure deeper insight. One may stand on a box and look over the heads of his fellows, but he no better sees the stars. The telescope and the microscope reveal depths which to the unassisted vision are closed. Yet not merely do they bring us no nearer to the cause of suns and animal-cula, but in looking through them the observer must shut his eyes to what lies about him. That intension is at the expense of extension is seen in the mental as in the physical sphere. A man of special learning may be a fool as to common relations. And that he who passes for an intellectual prince may be a moral pauper there are examples enough to show.

Book I, Ch. 2

Progress and Poverty (1879)

Kontext: It is too narrow an understanding of production which confines it merely to the making of things. Production includes not merely the making of things, but the bringing of them to the consumer. The merchant or storekeeper is thus as truly a producer as is the manufacturer, or farmer, and his stock or capital is as much devoted to production as is theirs.

“Now, however, we are coming into collision with facts which there can be no mistaking.”

Introductory : The Problem

Progress and Poverty (1879)

Kontext: At the beginning of this marvelous era it was natural to expect, and it was expected, that labor-saving inventions would lighten the toil and improve the condition of the laborer; that the enormous increase in the power of producing wealth would make real poverty a thing of the past. … It is true that disappointment has followed disappointment, and that discovery upon discovery, and invention after invention, have neither lessened the toil of those who most need respite, nor brought plenty to the poor. But there have been so many things to which it seemed this failure could be laid, that up to our time the new faith has hardly weakened. We have better appreciated the difficulties to be overcome; but not the less trusted that the tendency of the times was to overcome them.

Now, however, we are coming into collision with facts which there can be no mistaking. From all parts of the civilized world come complaints of industrial depression; of labor condemned to involuntary idleness; of capital massed and wasting; of pecuniary distress among businessmen; of want and suffering and anxiety among the working classes. All the dull, deadening pain, all the keen, maddening anguish, that to great masses of men are involved in the words "hard times," afflict the world to-day. This state of things, common to communities differing so widely in situation, in political institutions, in fiscal and financial systems, in density of population and in social organization, can hardly be accounted for by local causes.

Ch. 21 : Conclusion http://www.wealthandwant.com/HG/SP/SP22_Conclusion.htm

Social Problems (1883)

Kontext: More is given to us than to any people at any time before; and, therefore, more is required of us. We have made, and still are making, enormous advances on material lines. It is necessary that we commensurately advance on moral lines. Civilization, as it progresses, requires a higher conscience, a keener sense of justice, a warmer brotherhood, a wider, loftier, truer public spirit. Falling these, civilization must pass into destruction. It cannot be maintained on the ethics of savagery. For civilization knits men more and more closely together, and constantly tends to subordinate the individual to the whole, and to make more and more important social conditions.

Introductory : The Problem

Progress and Poverty (1879)

Kontext: I propose in this inquiry to take nothing for granted, but to bring even accepted theories to the test of first principles, and should they not stand the test, freshly to interrogate facts in the endeavor to discover their law.

I propose to beg no question, to shrink from no conclusion, but to follow truth wherever it may lead. Upon us is the responsibility of seeking the law, for in the very heart of our civilization to-day women faint and little children moan. But what that law may prove to be is not our affair. If the conclusions that we reach run counter to our prejudices, let us not flinch; if they challenge institutions that have long been deemed wise and natural, let us not turn back.

Introduction : The Reason for the Examination

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Kontext: The respect for authority, the presumption in favor of those who have won intellectual reputation, is within reasonable limits, both prudent and becoming. But it should not be carried too far, and there are some things especially as to which it behooves us all to use our own judgment and to maintain free minds. For not only does the history of the world show that undue deference to authority has been the potent agency through which errors have been enthroned and superstitions perpetuated, but there are regions of thought in which the largest powers and the greatest acquirements cannot guard against aberrations or assure deeper insight. One may stand on a box and look over the heads of his fellows, but he no better sees the stars. The telescope and the microscope reveal depths which to the unassisted vision are closed. Yet not merely do they bring us no nearer to the cause of suns and animal-cula, but in looking through them the observer must shut his eyes to what lies about him. That intension is at the expense of extension is seen in the mental as in the physical sphere. A man of special learning may be a fool as to common relations. And that he who passes for an intellectual prince may be a moral pauper there are examples enough to show.

Progress and Poverty (1879)

Kontext: There is, and always has been, a widespread belief among the more comfortable classes that the poverty and suffering of the masses are due to their lack of industry, frugality, and intelligence. This belief, which at once soothes the sense of responsibility and flatters by its suggestion of superiority, is probably even more prevalent in countries like the United States, where all men are politically equal, and where, owing to the newness of society, the differentiation into classes has been of individuals rather than of families, than it is in older countries, where the lines of separation have been longer, and are more sharply, drawn. It is but natural for those who can trace their own better circumstances to the superior industry and frugality that gave them a start, and the superior intelligence that enabled them to take advantage of every opportunity, to imagine that those who remain poor do so simply from lack of these qualities.

But whoever has grasped the laws of the distribution of wealth, as in previous chapters they have been traced out, will see the mistake in this notion. The fallacy is similar to that which would be involved in the assertion that every one of a number of competitors might win a race. That any one might is true; that every one might is impossible.

For, as soon as land acquires a value, wages, as we have seen, do not depend upon the real earnings or product of labor, but upon what is left to labor after rent is taken out; and when land is all monopolized, as it is everywhere except in the newest communities, rent must drive wages down to the point at which the poorest paid class will he just able to live and reproduce, and thus wages are forced to a minimum fixed by what is called the standard of comfort — that is, the amount of necessaries and comforts which habit leads the working classes to demand as the lowest on which they will consent to maintain their numbers. This being the case, industry, skill, frugality, and intelligence can avail the individual only in so far as they are superior to the general level just as in a race speed can avail the runner only in so far as it exceeds that of his competitors. If one man work harder, or with superior skill or intelligence than ordinary, he will get ahead; but if the average of industry, skill, or intelligence be brought up to the higher point, the increased intensity of application will secure but the old rate of wages, and he who would get ahead must work harder still.

Zdroj: Protection or Free Trade? (1886), Ch. 2

Kontext: When we consider that labor is the producer of all wealth, is it not evident that the impoverishment and, dependence of labor are abnormal conditions resulting from restrictions and usurpations, and that instead of accepting protection, what labor should demand is freedom. That those who advocate any extension of freedom choose to go no further than suits their own special purpose is no reason why freedom itself should be distrusted.

Zdroj: Social Problems (1883), Ch. 21 : Conclusion

Kontext: Those who are most to be considered, those for whose help the struggle must be made, if labor is to be enfranchised, and social justice won, are those least able to help or struggle for themselves, those who have no advantage of property or skill or intelligence, — the men and women who are at the very bottom of the social scale. In securing the equal rights of these we shall secure the equal rights of all.

Hence it is, as Mazzini said, that it is around the standard of duty rather than around the standard of self-interest that men must rally to win the rights of man. And herein may we see the deep philosophy of Him who bade men love their neighbors as themselves.

In that spirit, and in no other, is the power to solve social problems and carry civilization onward.

Zdroj: Protection or Free Trade? (1886), Ch. 6

Part I : Declaration, Ch. IV : Mr. Spencer's Confusion as to Rights

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Kontext: Men must have rights before they can have equal rights. Each man has a right to use the world because he is here and wants to use the world. The equality of this right is merely a limitation arising from the presence of others with like rights. Society, in other words, does not grant, and cannot equitably withhold from any individual, the right to the use of land. That right exists before society and independently of society, belonging at birth to each individual, and ceasing only with his death. Society itself has no original right to the use of land. What right it has with regard to the use of land is simply that which is derived from and is necessary to the determination of the rights of the individuals who compose it. That is to say, the function of society with regard to the use of land only begins where individual rights clash, and is to secure equality between these clashing rights of individuals.

Zdroj: Social Problems (1883), Ch. 21 : Conclusion

Introduction : The Reason for the Examination

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Conclusion : The Moral of this Examination

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

Zdroj: Social Problems (1883), Ch. 17 : The Functions of Government

Zdroj: Social Problems (1883), Ch. 13 : Unemployed Labor

as it is in things that are the proper field of the natural sciences to bow before the dictum of those who say, "Thus saith religion!"

Conclusion : The Moral of this Examination

A Perplexed Philosopher (1892)

“How can a man be said to have a country where he has no right to a square inch of soil…”

Zdroj: Social Problems (1883), Ch. 2 : Political Dangers