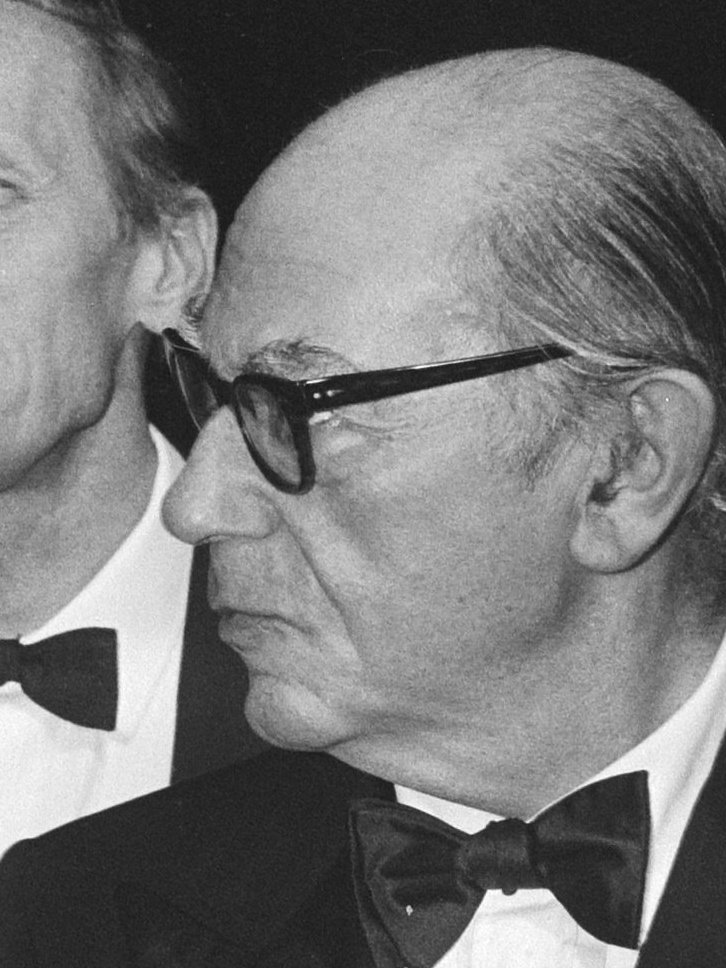

Isaiah Berlin citáty a výroky

Isaiah Berlin: Citáty v angličtine

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Introduction (1969)

Kontext: Those, no doubt, are in some way fortunate who have brought themselves, or have been brought by others, to obey some ultimate principle before the bar of which all problems can be brought. Single-minded monists, ruthless fanatics, men possessed by an all-embracing coherent vision do not know the doubts and agonies of those who cannot wholly blind themselves to reality.

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

Kontext: If, as I believe, the ends of men are many, and not all of them are in principle compatible with each other, then the possibility of conflict — and of tragedy — can never wholly be eliminated from human life, either personal or social. The necessity of choosing between absolute claims is then an inescapable characteristic of the human condition. This gives its value to freedom as Acton conceived of it — as an end in itself, and not as a temporary need, arising out of our confused notions and irrational and disordered lives, a predicament which a panacea could one day put right.

“Everyone knows what made Berkeley notorious. He said that there were no material objects.”

Berkeley’s External World (1947)

Kontext: Everyone knows what made Berkeley notorious. He said that there were no material objects. He said the external world was in some sense immaterial, that nothing existed save ideas — ideas and their authors. His contemporaries thought him very ingenious and a little mad.

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), From Hope and Fear Set Free (1964)

Kontext: Knowledge increases autonomy both in the sense of Kant, and in that of Spinoza and his followers. I should like to ask once more: is all liberty just that? The advance of knowledge stops men from wasting their resources upon delusive projects. It has stopped us from burning witches or flogging lunatics or predicting the future by listening to oracles or looking at the entrails of animals or the flight of birds. It may yet render many institutions and decisions of the present – legal, political, moral, social – obsolete, by showing them to be as cruel and stupid and incompatible with the pursuit of justice or reason or happiness or truth as we now think the burning of widows or eating the flesh of an enemy to acquire skills. If our powers of prediction, and so our knowledge of the future, become much greater, then, even if they are never complete, this may radically alter our view of what constitutes a person, an act, a choice; and eo ipso our language and our picture of the world. This may make our conduct more rational, perhaps more tolerant, charitable, civilised, it may improve it in many ways, but will it increase the area of free choice? For individuals or groups?

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

Kontext: I am normally said to be free to the degree to which no man or body of men interferes with my activity. Political liberty in this sense is simply the area within which a man can act unobstructed by others. If I am prevented by others from doing what I could otherwise do, I am to that degree unfree; and if this area is contracted by other men beyond a certain minimum, I can be described as being coerced, or, it may be, enslaved. Coercion is not, however, a term that covers every form of inability. If I say that I am unable to jump more than ten feet in the air, or cannot read because I am blind, or cannot understand the darker pages of Hegel, it would be eccentric to say that I am to that degree enslaved or coerced. Coercion implies the deliberate interference of other human beings within the area in which I could otherwise act.

“Knowledge increases autonomy both in the sense of Kant, and in that of Spinoza and his followers.”

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), From Hope and Fear Set Free (1964)

Kontext: Knowledge increases autonomy both in the sense of Kant, and in that of Spinoza and his followers. I should like to ask once more: is all liberty just that? The advance of knowledge stops men from wasting their resources upon delusive projects. It has stopped us from burning witches or flogging lunatics or predicting the future by listening to oracles or looking at the entrails of animals or the flight of birds. It may yet render many institutions and decisions of the present – legal, political, moral, social – obsolete, by showing them to be as cruel and stupid and incompatible with the pursuit of justice or reason or happiness or truth as we now think the burning of widows or eating the flesh of an enemy to acquire skills. If our powers of prediction, and so our knowledge of the future, become much greater, then, even if they are never complete, this may radically alter our view of what constitutes a person, an act, a choice; and eo ipso our language and our picture of the world. This may make our conduct more rational, perhaps more tolerant, charitable, civilised, it may improve it in many ways, but will it increase the area of free choice? For individuals or groups?

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

Kontext: If, as I believe, the ends of men are many, and not all of them are in principle compatible with each other, then the possibility of conflict — and of tragedy — can never wholly be eliminated from human life, either personal or social. The necessity of choosing between absolute claims is then an inescapable characteristic of the human condition. This gives its value to freedom as Acton conceived of it — as an end in itself, and not as a temporary need, arising out of our confused notions and irrational and disordered lives, a predicament which a panacea could one day put right.

“Philosophers are adults who persist in asking childish questions.”

As quoted in The Listener (1978)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Introduction (1969)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Introduction (1969)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

The Hedgehog and the Fox (1953). Editor Henry Hardy. Collaborator Michael Ignatieff. Editorial Princeton University Press, 2013. ISBN 1400846633, p. 2.

Essays in Honour of E. H. Carr (1974) edited by Chimen Abramsky, p. 9

Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas (1980), The Originality of Machiavelli (1971)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Political Ideas in the Twentieth Century (1950)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Historical Inevitability (1954)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Two Concepts of Liberty (1958)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), John Stuart Mill and the Ends of Life (1959)

Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas (1980), The Originality of Machiavelli (1971)

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Historical Inevitability (1954)

As quoted in Communications and History : Theories of Knowledge, Media and Civilization (1988) by Paul Heyer, p. 125

Five Essays on Liberty (2002), Political Ideas in the Twentieth Century (1950)